In this article

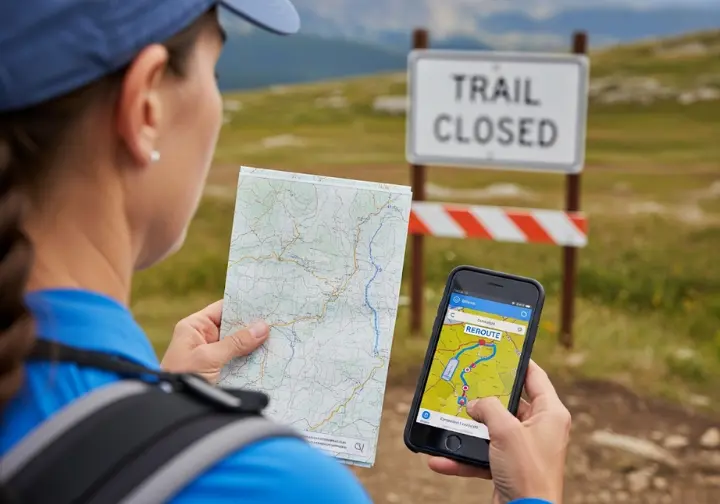

The sight is all too familiar: a perfectly planned hike, the car parked at the trailhead, boots laced, and then you see it—the stark, uncompromising “Trail Closed” sign. That wave of frustration is real, but it’s also a doorway. This guide will walk you through that doorway, transforming the immediate problem of how trail closures affect your hiking plans into a fascinating journey through trail science, proactive planning, and the essential role you play in the conservation of the wilderness.

We’ll master the art of the Plan B, learning the pre-hike checks and on-trail steps that ensure a closure never ruins your day outdoors. We’ll peek behind the sign to discover the critical reasons trails must be closed, from endangered species protection to preventing catastrophic trail erosion. You’ll go behind the scenes with the trail crews who practice sustainable trail building, creating durable new trail sections and expertly executing trail reclamation strategies on old, damaged paths. Most importantly, you’ll see how to shift from a simple hiker to a knowledgeable trail steward, understanding your role in preserving the wild places you love to trek.

The Hiker’s Dilemma: How Do I Deal With a Closed Trail?

This is where the rubber meets the trail, or in this case, where it doesn’t. Dealing with a closure isn’t just about disappointment; it’s about risk management and making a safe, smart, and ethical decision based on the best trail conditions information available. Your proactive planning for this problem begins long before you even leave the house.

What is the Best Way to Find Trail Closures Before I Hike?

In the world of outdoor planning and preparation, the ability to find trail information is your most valuable skill. To build a complete picture of your intended route, you must layer intelligence from several sources, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Your foundation, the gold standard for information, should always be the official land manager’s website. Whether it’s the U.S. National Park System alerts page for a trip to Death Valley National Park, a USDA Forest Service district page for the White Mountain National Forest, or specific park websites, this is where you’ll find the most authoritative closure orders. While incredibly reliable, be aware that these sites can sometimes have a slight delay in updating for sudden events.

Next, you add the real-time, on-the-ground layer from your digital toolkit. Crowdsourced apps like AllTrails and FarOut are invaluable for recent hiker reports. A user might post a photo of a washed-out bridge or new signage hours or even days before the official website reflects the change. The crucial caveat here is to treat this information as valuable intelligence, not gospel—it isn’t officially verified. Think of diversifying your sources beyond AllTrails as a core skill.

| Source Type | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Official Websites | Authoritative, most reliable for official orders | Potential lag in updates for sudden events | Final confirmation, official regulations, long-term planning |

| Trail Apps | Real-time user reports, photos, quick updates | Information unverified, potential for inaccuracies | Last-minute conditions, on-the-ground intelligence |

| Hiking Group Forums | Detailed info for specific long trails, community insights | Can be niche, information might be scattered | Long-distance trails, specific reroutes, community best practices |

| Ranger Stations / Visitor Centers | Latest on-the-ground intelligence, personalized advice | Limited hours, may require phone call | Absolute latest updates, specific questions, expert insights |

For long-distance or high-profile hiking trails, tap into community intelligence from hiking group forums. Dedicated trail associations like the Pacific Crest Trail Association (PCTA) or The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) maintain incredibly detailed closure and reroute information, often tailored to the specific needs of thru-hikers on a National Scenic Trail.

Finally, never underestimate the power of direct contact. The old-school method of picking up the phone and calling a local ranger station or visitor center remains one of the most reliable ways to get the absolute latest on-the-ground intelligence before you commit to the drive.

But even with the best planning, surprises happen. When you turn a corner and face that unexpected sign, knowing how to react safely and ethically is a core hiking skill.

What Should I Do When I Encounter a Closure on the Trail?

First, don’t panic or get frustrated. This is a moment of reactive adaptation. Stop in a safe place, well off the footpath if necessary, and take a moment. Read every word on the posted signage. It will often tell you the reasons for closure, the expected duration, and sometimes even suggest an official detour. This is your primary piece of intelligence.

Now, take out your map and compass or fire up your GPS app. This is the moment where preparedness pays off. Assess your options. Is there another trail nearby that can serve as an alternate route? Can you safely backtrack to your car and drive to a different trailhead? Making a good decision here is the essence of self-sufficiency, and our a hiker’s emergency guide covers the mindset needed to stay calm and make a safe plan.

Here we come to the non-negotiable rule: you must never, ever ignore a trail closure sign or enter a closure area. The reasons are threefold. First are the safety considerations. The hazard that closed the trail—be it rockfall danger in a canyon, a washed-out bridge, or aggressive wildlife—is often not visible from the sign. Second, you risk causing significant environmental impact. Your human activity can trample fragile new growth or stress wildlife during a critical period. Third, it’s a matter of legality and respect. Entering a closed area is often illegal trespass and can carry hefty fines, and it shows deep disrespect for the land managers and volunteers working to protect the trail.

Pro-Tip: Always carry redundant navigation systems. If your phone battery dies, your paper map and compass become your lifeline for finding an alternate route. Before your hike, trace your intended route on the paper map and take a moment to identify potential “escape routes” or connecting trails. This five-minute investment can save you hours of confusion.

For thru-hikers on long trails like the Appalachian Trail or Pacific Crest Trail, the challenge is magnified. A closure from a wildfire or hurricane can shut down a hundred-mile section, requiring complex logistics that often involve a long road walk or hitches from “trail angels” to bypass the area and continue the extended trip.

Respecting that sign is the first step. The next is understanding that it’s not an arbitrary barrier, but a necessary response to a wide range of powerful environmental causes.

Behind the Sign: Why Are Trails Actually Closed?

A “Trail Closed” sign is the end of a long decision-making process, a final, necessary action taken to protect either you, the trail itself, or the environmentally sensitive area it passes through. The reasons they go up are as varied and dynamic as the mountains, hills, and forests themselves.

What are the Key Environmental and Safety Reasons for Closures?

Nature often has the final say. One of the most common reasons for a closure is wildlife protection. Human presence, even quiet passage, can cause immense stress to animals during sensitive periods. A trail might be closed for a few weeks in the spring for seasonal closures for wildlife protection like elk calving, or to give an endangered species peace at their den. Disturbing them can lower survival rates for their young, a devastating impact for a simple walk.

Major natural disasters and the effects of climate change leave long-lasting scars that make trails impassable and dangerous for months or years. After a wildfire, the ground can be unstable and prone to flooding, and burned, standing trees (known as “hazard trees” or “widowmakers”) can fall without warning. In 2020, for example, it was reported that more than a third of the Appalachian Trail was inaccessible due to closures stemming from the pandemic, a reminder of how large-scale events impact our trail systems. Floods, excessive heat, and hurricanes can completely obliterate sections of trail, leaving them unsafe until they can be completely rebuilt. These are just some of the hazards specific to winter hiking, but they can occur year-round.

Sometimes, the reason is the trail condition itself. Hiking on deeply muddy trails, especially in the spring thaw, causes severe damage. Each footstep compacts the wet soil and deepens ruts, which then channel water and accelerate soil erosion, literally washing the trail off the hillside.

Geologic instability is another critical safety concern. Danger from rockfall, unstable slopes after heavy rain, or major washouts can close trails with little warning, as has been seen in places like Zion National Park or the canyons near Mt. Baldy where geology is an active, powerful force. Finally, closures can be enacted for resource protection, shielding a field of rare wildflowers from being trampled into oblivion or protecting an irreplaceable archaeological site from damage.

While nature often dictates when a trail must close, sometimes the reasons are more logistical, stemming from the very trail work required to keep the trail system healthy.

What are the Main Administrative and Maintenance Reasons?

If you see a sign that reads “Closed for Maintenance,” it’s for your safety and the safety of the trail crew. Active trail work, whether it’s new trail construction, setting stone steps, or replacing a bridge with a helicopter, creates a hazardous work zone. Closing the trail ensures that a hiker doesn’t wander into the path of a falling rock or a piece of heavy equipment.

Broader resource management activities also require temporary closures. A trail running through a section of forest slated for a timber harvest or a prescribed burn must be closed to the public. These actions, while disruptive in the short term, are often essential for the long-term health and safety of the forest ecosystem. An example of this is when land managers post trail closures for resource management like timber harvests to keep the public safe.

Less commonly, you might encounter a closure for public safety or special events. This can happen in extremely popular, heavily visited areas to manage overcrowding and its environmental impact, to clear the way for a trail marathon, or in the rare case of law enforcement activity in the area.

Seeing a trail closed for “maintenance” or a “reroute” is one thing; understanding the incredible science and labor that goes into that work is what truly builds appreciation.

The Science of Sustainability: How Are Trails Built and Repaired?

A trail is more than just a path of cleared dirt; it’s a carefully engineered structure designed to coexist with the forces of nature. The entire trail construction process, from planning to long-term trail maintenance, is guided by the principles of sustainable trail design and sustainability. When that design fails, or when a trail was never properly designed in the first place due to unsuitable trail siting, land managers and volunteers step in with science and sweat to make it right.

What Makes a Trail “Sustainable”?

A sustainable trail is one that lasts for generations with minimal maintenance because it’s built in harmony with the landscape. This is accomplished through proper trail planning, design, construction and maintenance. The primary enemy of every trail is water. A poorly designed trail—often one that runs straight up a hill, known as a “fall-line” trail—acts like a gutter. Rainwater flows directly down its center, gathering speed and power, stripping away soil, affecting water quality downstream, and carving a deep, ugly trench.

To defeat water, sustainable trail design follows a few core trail design principles. First, trails are built on the contour of a slope, like a set of stairs wrapping around a mountain instead of going straight up. This “side-hill” design encourages proper drainage. Second, trail crews build in subtle features using durable trail construction materials like rocks and timber to manage the water that does land on the trail. A “grade reversal” or “rolling dip” is a slight dip followed by a rise in the trail that acts like a tiny speed bump, gently ejecting water off the side before it can cause damage.

This is also why “social trails,” those user-created shortcuts that cut switchbacks, are so destructive. They are almost always unsustainable fall-line trails that ignore these principles, leading to severe erosion from increased foot traffic and fragmenting sensitive habitats. The key to a long-lasting trail is not just building it, but actively maintaining them with these principles in mind.

These principles are the foundation. When an old, unsustainable trail fails, crews apply this science to build a better, more resilient path and rebuild or reroute it.

How Are Old, Damaged Trails Properly Closed and Reclaimed?

Reclaiming abandoned trails is a complex process, far more involved than just blocking the entrance. As the USDA Forest Service notes in its Trail Construction and Maintenance Notebook, simply putting up a sign or piling brush at the trail entrance fails because the compacted soil and clear sight line continue to invite use for decades. Proper restoration projects require a full suite of trail reclamation strategies: closure, stabilization, recontouring, revegetation, and monitoring.

The first step is to decompact the treadway. Crews use tools to break up the rock-hard surface that has been pounded down by thousands of boots, allowing air and water to penetrate once again. Next comes recontouring the slope, pulling soil from the outer edge back into the trail bed to erase the man-made bench and restore the hill’s natural angle and drainage patterns.

Finally, they actively disguise the corridor to encourage natural revegetation. This can involve scattering native leaf litter and fallen boulders to make it look like the surrounding forest floor, and planting native seeds or seedlings to kickstart the healing process. In very steep, eroded gullies, crews may install check dams—small barriers of rock or wood—to stabilize the soil and trap sediment, slowly rebuilding the lost ground. It’s a painstaking process.

This intensive work—requiring immense cost and volunteer effort—highlights that trails are not just paths, but valuable community assets that require active trail stewardship from all of us.

From Hiker to Steward: What is My Role in Trail Preservation?

Every time you step onto a trail, you become part of its story. Your actions, big and small, can either contribute to its decline or ensure its longevity. The shift from hiker to trail steward begins with understanding this connection and ends with taking positive action.

How Do My Actions Connect to Trail Closures?

The connection between your choices and the environmental impact on trails is direct and powerful, and it’s beautifully summarized by The 7 Principles of Leave No Trace. “Plan Ahead and Prepare” isn’t just about packing the ten essentials; it means doing your homework and checking for closures before you go. “Travel on Durable Surfaces” is the perfect example of trail stewardship in action. When you encounter a muddy section, the correct choice is to walk straight through the middle. Walking around the mud widens the trail, tramples vegetation, and creates a bigger problem for the future. It’s a small, muddy sacrifice for the long-term health of the trail.

Pro-Tip: Turn your smartphone into a stewardship tool. If you encounter a significant new issue on a trail, like a large fallen tree or a washed-out culvert, take a photo and use a GPS app to get the exact coordinates. Emailing this precise information to the local land manager is incredibly helpful and can speed up the repair process.

Respecting a closure is a form of “Be Considerate of Other Visitors,” as it sets a positive example and prevents the herd mentality that can lead to widespread damage. By mastering outdoor ethics, you become an active partner in preservation.

There’s also an economic reality. Trail maintenance is expensive, with annual costs running anywhere from $500 to over $3,900 per mile depending on the trail type. A preventative closure during mud season can save thousands of dollars in repair costs down the line. When you consider that trails are powerful economic engines, as shown by studies on the economic benefits of trails in Washington State that document billions in annual spending, protecting them becomes a community-wide imperative.

Understanding your impact is the first step. The next is channeling that understanding into direct, positive action.

How Can I Get Involved and Help Maintain Trails?

One of the most rewarding steps you can take in your hiking journey is to spend a day giving back to the trails that have given you so much. Volunteering with a trail crew is an incredible experience that connects you to the land in a profound way and contributes directly to local trail development and conservation projects.

Finding opportunities is easy. National and regional trail associations like the Washington Trails Association (WTA), the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), and The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), along with agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and non-profits like Rails to Trails Conservancy, all host regular trail work events.

You don’t need any experience. A good attitude and a willingness to get a little dirty are the only prerequisites. The crew leaders provide all the necessary tools, safety gear, and expert trail-building knowledge. You might spend the day clearing fallen trees, using a grub hoe to dig new tread, or building rock water bars to manage erosion. It’s hard work, but the sense of accomplishment and the community you build with fellow volunteers is immense. It’s a natural next step in your growth as a hiker, much like transitioning from day hiker to backpacker.

Conclusion

A closed trail sign is a lesson, not a rejection. It teaches us that respecting trail closures is a non-negotiable act of safety, legality, and ecological responsibility. It reveals that the best trails are scientifically designed to manage water and minimize erosion, the very reason old paths must be rebuilt or rerouted. It reminds us that trails are valuable community assets, and that preventative closures are fiscally responsible decisions. The most powerful tool a hiker has is knowledge. Understanding the “why” behind a closure transforms you from a frustrated user into an informed trail steward, an active participant in the preservation of the wild.

Explore our complete library of Trail Skills guides to continue building your confidence and competence in the outdoors.

Frequently Asked Questions about Trail Closures and Reroutes

Can I hike a closed trail if I think it looks safe?

No, you should never hike a closed trail. Beyond the visible reason for closure, there can be unseen dangers like unstable ground, post-fire hazards, or aggressive wildlife, and entering a closed area is often illegal and can result in fines.

What’s the difference between a reroute and a detour?

A reroute is a permanent, newly constructed section of trail that replaces an old, unsustainable, or damaged section of backcountry trails. A detour is a temporary path, often using existing trails or roads, to guide hikers around a short-term closure.

Why do trails close when they are wet or muddy?

Hiking on saturated trails, especially those with clay soil, causes deep ruts, compacts the soil, and massively accelerates erosion. This “trail braiding” (widening the trail to avoid mud) destroys the trail tread and surrounding vegetation, requiring costly repairs.

How much does it really cost to maintain a hiking trail?

Annual trail maintenance costs can range widely, from $500-$1,000 per mile for softer-surface trails to over $3,900 per mile for more developed paths. This substantial cost is why land managers use preventative closures to protect the trail from expensive damage.

Risk Disclaimer: Hiking, trekking, backpacking, and all related outdoor activities involve inherent risks which may result in serious injury, illness, or death. The information provided on The Hiking Tribe is for educational and informational purposes only. While we strive for accuracy, information on trails, gear, techniques, and safety is not a substitute for your own best judgment and thorough preparation. Trail conditions, weather, and other environmental factors change rapidly and may differ from what is described on this site. Always check with official sources like park services for the most current alerts and conditions. Never undertake a hike beyond your abilities and always be prepared for the unexpected. By using this website, you agree that you are solely responsible for your own safety. Any reliance you place on our content is strictly at your own risk, and you assume all liability for your actions and decisions in the outdoors. The Hiking Tribe and its authors will not be held liable for any injury, damage, or loss sustained in connection with the use of the information herein.

Affiliate Disclosure: We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. We also participate in other affiliate programs and may receive a commission on products purchased through our links, at no extra cost to you. Additional terms are found in the terms of service.